It really is a shame Mighty Avengers has been saddled with the artwork of Greg Land. The script by 2000 A.D. alum Al Ewing delivers a better straightforward superhero narrative than Marvel has produced since Peter Parker: Spider-Man under Paul Jenkins, Mark Buckingham, and Humberto Ramos. None of the cloying cuteness of Daredevil or Hawkeye, none of the unimaginative snark of Brian Bendis’ Guardians of the Galaxy, and none of the portentous, elitist posturing of Jonathan Hickman’s Avengers books. Mighty Avengers #3: No Single Hero is old-fashioned in its depiction of good guys on the job, working towards common good.

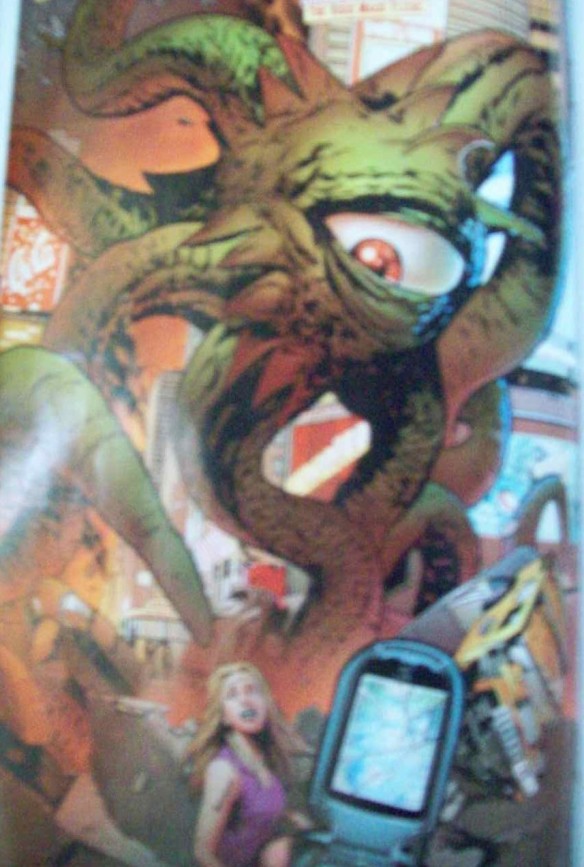

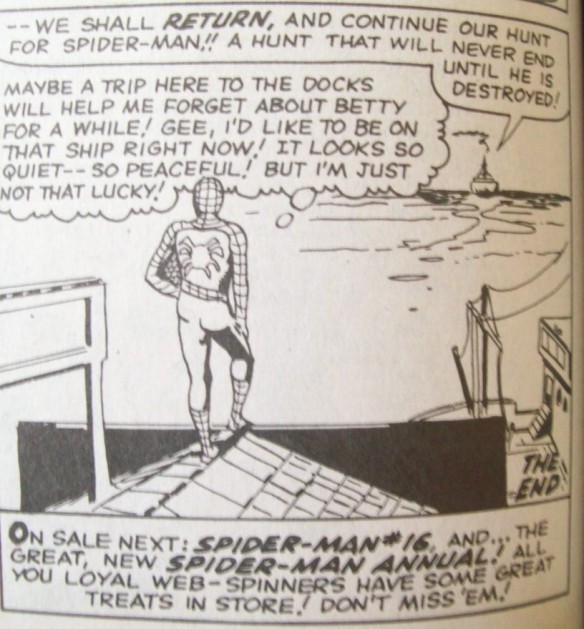

Much of Ewing’s writing, in fact, seems a reaction to Hickman’s Avengers/New Avengers/Infinity mega-arc. Where Hickman goes for godlike awe at his monolithic superteam (like Grant Morrison and Howard Porter’s JLA), Ewing stresses humanity, whether it’s the class-based bickering of “Superior” Spider-Man (Dr. Octopus having hijacked Peter Parker’s body) and “Spider Hero” (who is, apparently, Blade the Vampire Hunter in disguise)–ironically, Octopus calls Spider Hero an “impostor”–or a rooftop bonding moment between Power Man and White Tiger before entering the fray against alien invaders (showing an almost Shane Black-level of efficient scripting). Where Hickman is unconcerned with the “countless” death tolls incurred by his extraterrestrial threats, Ewing shows characters deliberately avoiding casualties (stalling for time when civilians are possessed by Lovecraftian terror Shuma-Gorath). Where Hickman is building the Avengers into a Homeland Security super-gestapo (Watchmen minus the moral compass; The Ultimates minus the satire), Ewing suggests reclaiming the super-hero as a model of populist sentiment–the choice of black, Hispanic, and working-class characters as the good guys, with Dr. Octopus-Spider-Man as an unlikeable crony capitalist and odd man out, harkens back to Roger Stern. Stern’s one-time Captain Marvel Monica Rambeau, here dubbed “Spectrum,” is again de facto team leader, putting a stop to the Spider-bickering and dealing the finishing blow to Shuma-Gorath.

This classicism is surprising from Ewing, who previously went for the jugular against vigilante tropes in the Garth Ennis work-for-hire book Jennifer Blood and the psychedelic spoof Zaucer of Zilk with Brendan McCarthy. And yet, doing so perfectly undermines Hickman’s surveillance state apologia: when White Tiger says she wants her death to “mean something,” Power Man gives a Dalton Trumbo response (“Death don’t ever mean anything. It’s just some &#$% happens to you one day”), promoting life as Hickman’s pretentious “To protect a world, you must possess the power to destroy a world” deals death.

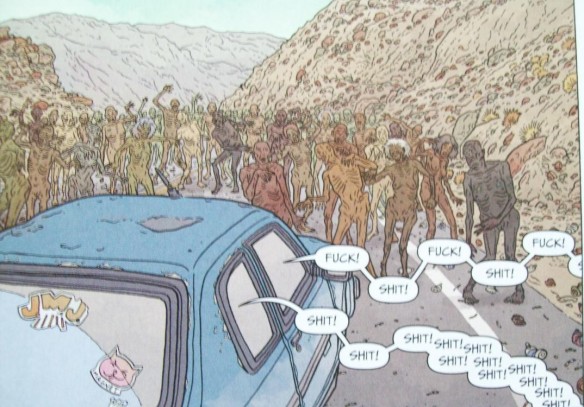

Ewing’s populism never quite overcomes the elitism of its sibling Avengers books, even if it’s a start. Luke Cage gives a rousing speech to a crowd of civilians on how “we are all Avengers,” yet we only see civilians acting in the previous issue to No Single Hero. Here, bystanders are reduced to either brainwashed masses or Cloverfield Millenials, capturing video on smart phones (a passive form of grassroots activism). Then there’s the depiction of Hickman-esque hyper-power–Blue Marvel and Spectrum–as being key to successful super-heroics, if not to the absurd degree shown in those charts-and-graphs-obsessed books. But, like fellow Brit China Miéville, Ewing understands the power of identity, the universal strength of community: Spider Hero gives advice to Power Man on summoning his chi, connecting “home and family” to “streets and landmarks” to “New York City”–“It all has power.”

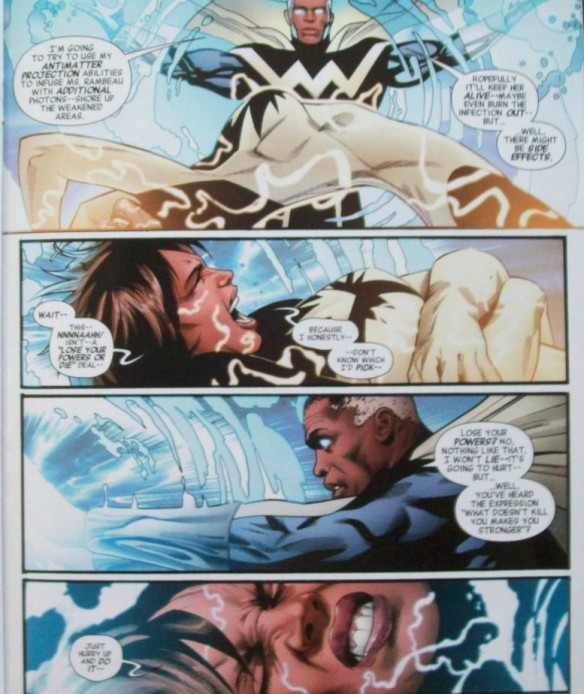

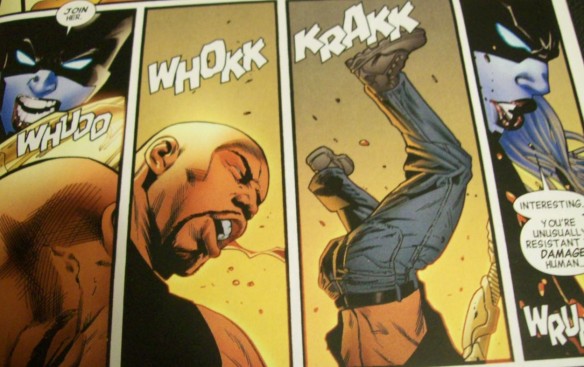

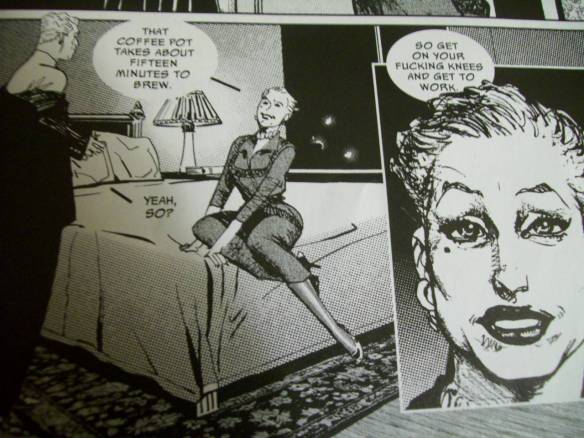

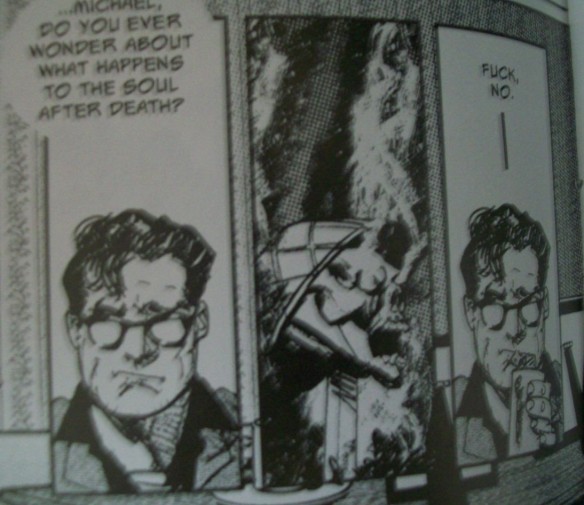

It’s to the credit of Ewing as a writer the scene, as with the comic, manages to scrape by. Greg Land depicts it with flatness, two closeups on Spider Hero and Power Man against nondescript color backgrounds. A more virtuosic artist like Emma Rios would have deployed fragmented, aspect-to-aspect grids (as she does in Pretty Deadly). Then again, Land’s style has been all wrong for this series: his stiff, Uncanny Valley figures always seem to display inappropriate emotion (Blue Marvel’s eerie grin when he heals Spectrum from a life-threatening wound), even when he’s not tracing what looks like still-frames from porn.

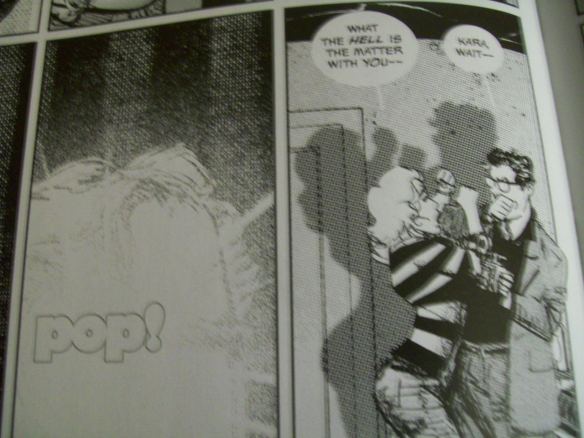

Land is unaided by colorist Frank D’Armata, who changes his palette after a decade of murky, ugly schemes which made several comics near-unreadable. Together, the two lighten the skin tones of the main characters, while depicting crowds of middle-class white folks, deflating Ewing’s inclusive “We are all Avengers” theme. Ewing’s no stranger to bad, incongruous art: Jennifer Blood labored under the oddly-plain exploitation of Dynamite artist Kewber Baal. Blood, however, had an interesting tension between Baal’s style (which followed mainstream comics trends) and Ewing’s sardonic observations, which put the series in Steve Gerber territory (Foolkiller, particularly). Land and D’Armata are there as a connection to the Brian Bendis/Joe Quesada house style/regime which Jonathan Hickman inherited and Ewing is backup for.

The art gets in the way of theme, rather than illustrate it, leaving No Single Hero only with words. Well-written, thoughtful words, but fighting a battle it barely wins with its own partner.