Upgrade

A movie that looks made for the square, 4:3 format of pan and scan VHS, Leigh Whannell’s Upgrade oozes paranoia. Logan Marshall-Green’s Grey Trace is a Luddite in a wireless, hands-free near-future, fixing up vintage muscle cars for the rich while rebuffing his smiley wife’s pleas for him to go modern. When he’s crippled by thugs who kill his wife, he’s enticed by a creepy Elon Musk-type into having a chip implanted that helps him walk again–the catch being it comes with a chatty A.I., STEM, that urges him towards revenge. Where the similar one-body buddy dynamic of Venom steers towards affable, scenery-chewing hijinks, the relationship between STEM and Grey is one at arm’s length. The voice in Grey’s head is calm, logical, insisting the path they take is the correct one. It breaks down his apprehension, eventually gets him to enjoy the privilege of superhuman mobility and the capacity to rend apart lesser beings, before pulling the rug out. By then, the power dynamic has shifted, Grey’s dependence exposing him to the exact nightmare his previous low-tech worldview was intended to protect him from.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

Despite suffering the same third act, glowing MacGuffin finale as its live-action brethren, Spider-Verse‘s approach to superheroes is far more exciting. Origins are communicated in punchy shorts riffing on Spider-Man’s stock imagery, a community built out of a shared sense of alienation. Action and comedy, similarly, flesh out the personalities of the movie’s various Spider-People, their enemies, allies, and civilians through movement, their stories and motivations crystal clear even when the slick, glossy mashup of graffiti and comics explodes across the screen. Directors Peter Ramsey, Bob Perischetti, and Rodney Rothman have constructed something special. You almost regret the inevitable attempts to replicate it.

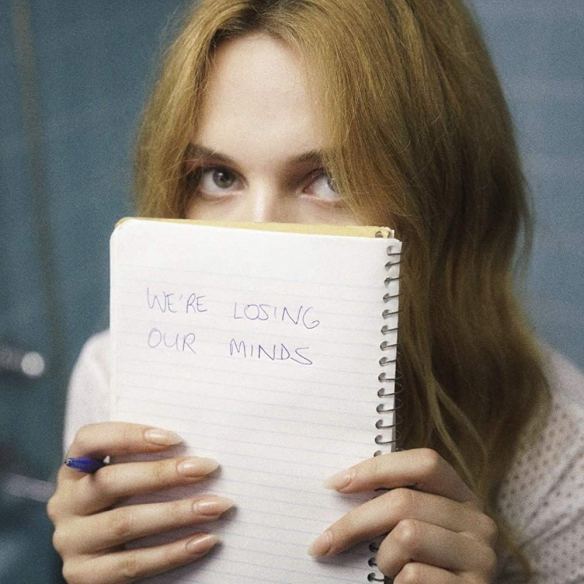

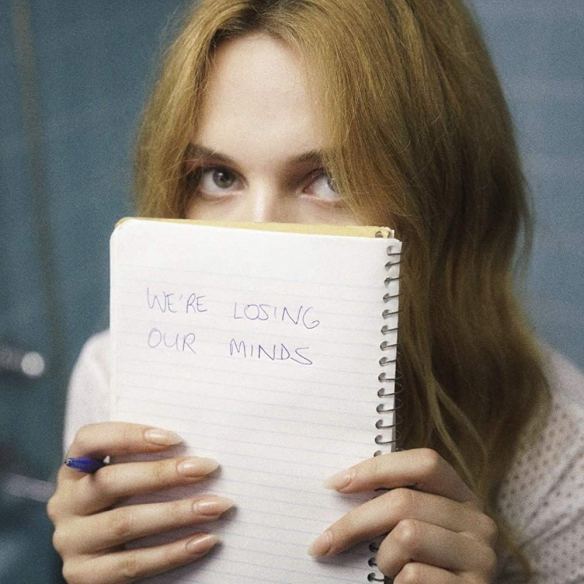

Assassination Nation

Assassination Nation excels at winding up tension. Small town America is hacked, its secrets leaked out for all to see, resulting in its people losing their goddamn minds. Crucially, every ugly, hateful thought crossing their minds is let off the leash, justified as reclaiming their dignity. Naturally, this culminates with all the boys targeting women. Specifically, Odessa Young’s Lily Colson. Lily–outspoken, creative, passionate, and intelligent, though tormented by her own demons–is first a spectator to this madness, her sober thoughts on the unfolding events dismissed by everyone caught up in a witch hunt; then a subject, as her own secret affair with an older man becomes fodder for the same people to project their personal brands of misogyny on her: an on/off boyfriend attempts to regain ownership of her through ruining her life; random men catcall and assault her; her own parents cast her out in the streets, unconcerned with her well-being until (hypocritically) the film’s close. Then, they all come to kill her and her friends. Sam Levinson captures the sickening realization of watching people you loved, and thought loved you, call for your blood. When Lily takes up an assault rifle and turns on her would-be killers, you’re right there with her. This is America: burn it to the fucking ground.

Sorry to Bother You

Boots Riley’s movie debut shares a key quality with Shane Black’s The Nice Guys. Both films take a standard film plot, twist and tangle it until it’s barely recognizable, then pull it all back together for a satisfying conclusion. The rabbit holes Sorry to Bother You wanders down, however, are more expansive, more brazen in mixing sci-fi and magical realism with a subverted rags to riches story. Cash (Lakeith Stanfield) is able to rise the corporate ladder at his telemarketing firm off his ability to mimic a nasally white man’s voice, but rather than freeing him, it only traps him further. He cuts himself off from his fellow workers, and discovers the bourgeoisie he interacts with regard him only as a commodity to exploit in a growing class war. The movie not only diagnoses the problem of capitalism, it posits a militant solution with equally biting humor.

First Reformed

Most of the time, crises of faith in movies are centered around the question of God’s existence or why He allows evil. Usually some tragedy befalls the central character that shakes their belief, which the subsequent three acts will resolve with renewed faith. First Reformed isn’t interested in such routine. Father Toller’s (Ethan Hawke) discovery of the corporate polluters behind the megachurch he is adjunct to, and the celebrations of the historical church he presides over, doesn’t shatter his beliefs. Instead, his crisis becomes one of his actions, as a Christian, in a world on the brink of environmental collapse. Paul Schrader connects this physical sickness (both the earth and Toller himself, suffering cancer) with a kind of spiritual rot: in addition to the moneyed interests he is in conflict with, Toller finds himself against people who regard religion as a product to consume. He gives tours of the church ending in a gift shop, for which he is tipped in one insulting moment. The faith he uses to understand the world and uplift humanity is in danger of becoming a mere possession. Schrader, ultimately, is asking if there’s any return from this kind of brink.

Also Liked: Thoroughbreds, Isle of Dogs, Apostle, The Maze Runner: The Death Cure, Venom, Crazy Rich Asians, Rampage, You Were Never Really Here, Mission: Impossible – Fallout, The Night Comes for Us, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs