Mythopolis #1

Art by Marco Turini

Writing by Richard Emms

Published by Ardden

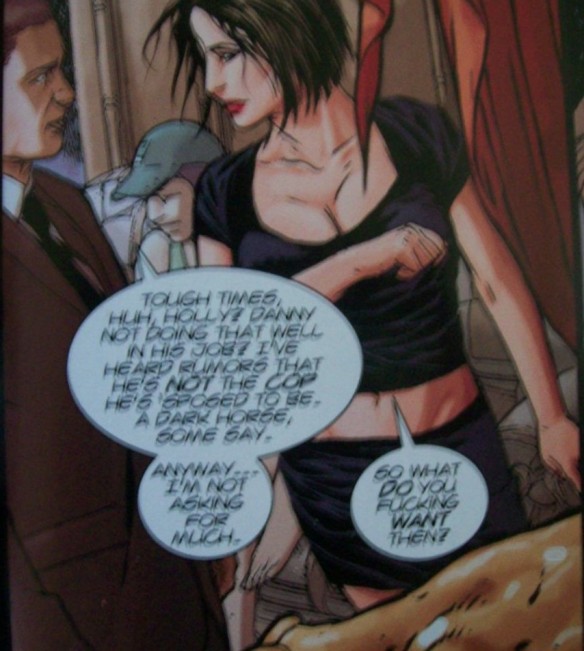

The title “Mythopolis” conjures up an image of urban fantasy. Where the modern and the mundane collide with the ancient and the fantastical. Yet, apart from its unheralded cliffhanger page, Mythopolis the comic isn’t about this. It isn’t even about what is actually depicted in the comic’s bulk: the plotless, clubfooted heist/revenge thriller spread between nearly a dozen characters (two of which are bald white men with goatees Marco Turini took the liberty of drawing exactly alike, which gets fun when one of them is killed) never remotely threatens to be interesting, even with a ticking clock counting down along the bottom of each page. The counter teases a Revelations-level apocalypse, while a love triangle between crooked cop Danny, prostitute Holly, and corporate slimeball/mayoral candidate Jacob has inklings of a class warfare version of Othello. Richard Emms’ script, however, fails to connect with any mythic connotation, doesn’t indicate any stakes beyond mysterious “product” being shipped and/or stolen, then stops with three hours on the clock and nothing of substance gleamed. The personalities are vacuous and cliched (Jacob, get this, publicly claims affection for New York City while privately bashing the city), the motivations nebulous (a Tokyo businessman talks about revenge for a slain son, but against who or even what happened are not even hinted at), and themes are noticeably absent. Like the happily-mediocre products of Robert Kirkman and Bill Willingham scripts, Mythopolis aims, presumably, for a late night cable spot–Emms even uses terms like “episodes” and “pilot” to describe the series–yet can’t be bothered with a coherent pitch. It conjures nothing.

The Wake #5

Art by Sean Murphy

Writing by Scott Snyder

Published by Vertigo

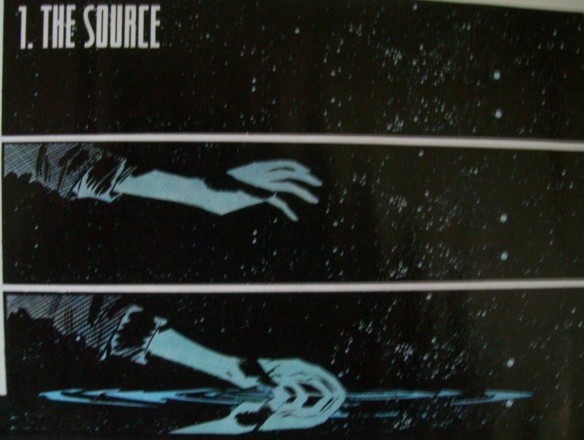

The first three panels Sean Murphy draws, depicting oceanographer Lee dipping her hand into seawater reflecting a starry night sky, are more literary than every other page published in The Wake thus far. Murphy obliterates the horizon, melding sky and sea together to suggest a continuum of existence, with the ocean as past and space as future. Lee, humanity’s present, reaches out like Michelangelo’s Adam, seeking the origins of her existence (the chapter is titled “The Source”). This subtle grandiosity becomes symbolic of the issue’s bulk, which demarcates Lee’s flashback from the closing page of dystopian descendant Leeward suiting up to explore a flooded city (her hand in the page’s first panel would be receiving Lee’s if the two images were side by side). In some ways, it follows the trajectory of Murphy’s blasphemous, brilliant Punk Rock Jesus, with the mother passing the baton of narrative to child–directly to Lee’s son Parker in a tearful goodbye, indirectly to Leeward. The Wake is less effective in its handoff, investing its first five issues (Jesus‘ entire length) to an often nonsensical, formulaic monster movie plot and complete ciphers–once again, Scott Snyder uses High-Concept exposition to relate myths (this time the Great Flood) to the plot, satisfied with merely surfing the web for ideas. In spite of this ever-literal script, Murphy approaches Kirby’s Kamandi, The Last Boy on Earth in communicating cosmic and humanist ideas, exploring the tension between them (his slender panel of a damaged submersible sinking to the depths is gripping). These moments almost make The Wake worth the hype.

Catwoman #25

Art by Aaron Lopresti

Writing by John Layman

Published by DC

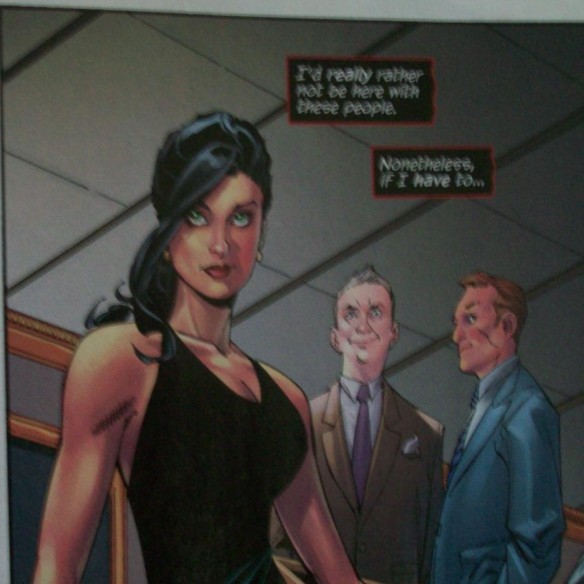

Since it’s been a whole issue since Catwoman had a crossover, DC has seen fit to throw it into Zero Year. Much of this reeks of last minute desperation, with Aaron Lopresti and John Layman pinch-hitting for Ann Nocenti and Rafa Sandoval mid-arc. The difference is night and day: Lopresti is strictly late 90s house style, but he is much more successful depicting Gotham City than he was with Gemworld over in Sword of Sorcery (for starters, he populates his backgrounds with people to give a sense of life beyond the walls of plot), while Layman casts aside his Chew humor in favor of a yeoman’s touch. He follows Nocenti’s populist outrage (his Catwoman expresses disgust at the extravagance and debauchery of a billionaire’s party) and how it relates to the anti-heroine’s Robin Hood-justification (slightly more conscious than the gas-stealing ninja in Occupy Comics). What Layman lacks, however, is the commitment of Nocenti’s voice, articulating modern Progressive ideals Gang War and Down Under which subverts DC’s larger, more reactionary trends (notably, her scripts are some of the few superhero works which pass the Bechdel Test, an achievement noticeably lacking with Layman). And while Lopresti is game for scenes of Selina Kyle punching and kicking corporate thugs, he’s at a loss with those involving the socialite party. He’s neither excessive with those panels to capture her repulsion/fascination (she takes up a whip, saying it “feels right”)–the way Rafa Sandoval stretched limbs to and skewed perspectives for psychological, funhouse affect–nor implicating enough upper-class horror. Lopresti leaves Layman stranded halfway to noir and unable to commit to the cause, right where DC wants its hired hands.